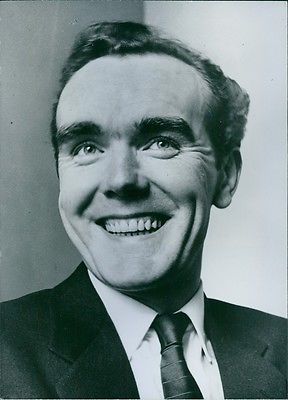

Edmund Tracey

(1927-2007), BA (Oxon), musician, critic, artistic director, translator and

dramaturge.

|

|

Artistic director whose adventurous stagings and fine translations

underpinned the successes of English National Opera. The distinguished

translator, critic and dramaturge Edmund Tracey was an éminence grise behind

the successes of English National Opera in the 1970s and 1980s. James Edmund Tracey, born 14 November 1927 Preston, Lancashire and

died London 23 March 2007, the son of James Tracey and Annie Whelan who were

married in 1916 in Bolton. He was educated at St. Mary's College grammar school in Blackburn, At

grammar school, heacquired his love of literature and cinema and, quite

unprompted, made up his mind that he was going to Oxford. The headmaster,

discussing his future with his mother, said that he supposed Jimmy (as he was

then known) would go into a local bank when he left school, to which she

retorted: "If you think that, you obviously don't know my son."

Instead, he wrote, off his own bat, to the provost of Oriel, receiving a

courteous reply to the effect that the college was likely to be full of

returning ex-servicemen, but he was passing the letter to his friend the head

of Lincoln College. He won a scholarship in 1945 to Lincoln College, Oxford,

where he read English and composed incidental music for undergraduate

productions, and called himself by his second name Edmund. After Oxford he

worked in London in the theatre as composer and music adviser, before

enrolling at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where he played the viola

and studied composition with Benjamin Frankel, earning money by working

nights at the international telephone exchange. He gradually recognised that

he was not cut out to be a composer. He then turned to criticism, starting

with film but soon moving to music. From 1958 he was number two to Peter Heyworth on The Observer and

music editor of the Times Educational Supplement, 1959-64. He also served on

the editorial board of Opera magazine. His notices were elegant and

trenchant, and betrayed deep knowledge of music and, in particular, opera. |

Tracey was passionate about opera, but his standards were impossibly

high, and he routinely gave performances at Sadler's Wells a slating. In 1965

Stephen Arlen, general manager of SWO, invited him to lunch and offered him a

job, to see if he could do any better. Tracey took up the challenge and started

his new career by improving the programmes.

The following year he and Arlen were discussing the future repertory and

decided to commission another opera from the Australian composer Malcolm

Williamson, whose first opera, Our Man in Havana, had been successfully

performed by the company in 1963. The new work was to be suitable both for

young people and adults and Tracey was asked to provide the text.

His first idea was a Dick Whittington, but Williamson did not approve,

and suggested a fairy-tale play by Strindberg, Lucky Peter's Journey. Tracey

wrote a three-act libretto, which Williamson duly set. The opera was given its

premiere on 18 December 1969. Though strongly cast and well performed, it was

not a success. The original play was pure fantasy, and Tracey had tried to

introduce some realism, but neither children nor grown-ups in the audience

enjoyed it. From then on Tracey concentrated on translating.

Nineteen seventy was the Beethoven bicentenary and "Sadler's Wells

at the Coliseum" staged Leonora (the first version of Fidelio) in March

and Fidelio itself in November. Tracey wrote new dialogue for both.

In August, between the two Beethoven works, a new production of

Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann was given, in a performing edition by Tracey

and Colin Graham, the director. Tracey made a new translation for the

production, which was a tremendous success. Next Tracey translated La traviata

(1973) and Massenet's Manon (1974), both very well received. By now the company

had finally become English National Opera.

Tracey provided new dialogue for Offenbach's La Belle Hélène and

Mozart's The Seraglio, then in February 1976 he made the translation for a new

production of Tosca. After providing English Music Theatre with a translation

of Mozart's La finta giardiniera - literally "The False Lady

Gardener" - which was given as Sandrina's Secret at Sadler's Wells

Theatre, Tracey worked on a new version of Verdi's Aida, which was performed by

ENO in 1979. Meanwhile he wrote new dialogue for two operettas, Johann

Strauss's Die Fledermaus and Lehar's The Merry Widow. Christopher Hassall

translated the lyrics in both cases.

In 1981 Tracey translated Gounod's Romeo and Juliet and Charpentier's

Louise; he also adapted his version of The Tales of Hoffmann for a production,

very different from ENO's, at Opera North.

Verdi's The Sicilian Vespers followed in 1984, then in 1985 Tracey made

one of the most successful of all his adaptations: Gounod's Faust. Returning to

the original version with dialogue, Tracey and the director Ian Judge made a

performing text that brought the old warhorse/masterpiece to vigorous new life.

His Faust translation was also used by the New Sussex Opera Company at the

Brighton Festival in 1989. Tracey finally retired in 1993.

Despite his strong personality and charismatic charm, Tracey was in some

ways a very private person; but those who worked for him and those who knew him

well loved him. To them he was a wise friend and captivating companion, with a

native Irish genius for storytelling, a near-perfect memory, a natural talent

for attracting bizarre happenings and strange encounters, a mind full of

unpredictable ideas, and a rare way with words, which made conversation with

him a delight. During his long final illness (he suffered from Parkinson's

disease), he showed a patience and fortitude that won the admiration of friends

and nursing staff alike.

This is how Henrietta Bredin in The Spectator described his funeral:

“Edmund Tracey RIP

Memorial services. Difficult to get right but potentially celebratory,

contemplative, comforting and spiritually sustaining. Earlier today, St Paul's

Covent Garden saw a gathering that was all of those things, in memory of Edmund

Tracey, a wise, witty and gloriously cultivated man, Literary Manager for many

years at Sadler's Wells, then at English National Opera. He worked in happier

times for that beleaguered company and a splendid assembly of singers,

conductors, directors and numerous others came together to celebrate him. I can

think of fewer more thrilling experiences than adding one's own piping tones in

'Immortal invisible' to the soaring notes of Dames Josephine Barstow and Anne

Evans, backed up by Graham Clark's Wagnerian tenor, with Martin Neary at the

organ. Wonderful.”

Filmography:

1980 The Merry Widow - Dialogue

1976 Die Fledermaus - English version

Ref:

Lincoln College News, August 2008

Opera, June 2007

The Guardian, 25 April 2007

The Independent, 4 April 2007

The Spectator, 1st November 2007

The Stage 21 May 2007

The Times. May 2, 2007

Last update: 03

November 2016