HOME

Uí Bairrche (Leinster) –

Page 1

Uí Bairrche – Page 1:

Origins and History

Saints and Monastic Settlements

Family

groups and settlements

Ancient Genealogy of the Úi Bairrche (taken from Rawlinson B502, Book of

Leinster, Book of Lecan, Book of Ballymote, hagiography and the Annals)

Origins

and History

The Uí Bairrche (Huib Airrchi, Crioch mBairce, Uí Bairche, hói Bairche, Uí Bairchi, Bairrce, Ua mBairrche, Chirch Om-Bairrche, mBairrchi, oi baiȓ, Oe-Barche, mBarchi, Barraidh, Úa mBarrche, Barrchi, Barridie, Uí Barrtha, mBerriuch) were an important Leinster dynasty. They ruled Leinster in the earliest centuries A.D.

It may be that the tribal name came from Sobairce, an early High King of Ireland. Sobairce and his brother Cearmna Finn, were joint rulers over Ireland, one in the north and the other in the south. They were the sons of Ebric, son of Emher, son of Ir, son of Míl Espáine, They were the first High Kings to come from the Ulaid. Sobairce resided on the north coast of Antrim, at Dun Sobairce (Dunseverick alias Feigh in the civil parish of Billy Co. Antrim). Of interest, there are no decendants listed in the genealogies. Nearby, to the east on the coast, there is the civil parish of Culfeightrin Co. Antrim, where there is the fort or tomb of Burach or Barrach, a Red Branch knight, located at Torr Head. In the same civil parish, there is the river Margy and the townland of Bonamargy.

|

In the ancient Irish genealogies, and as they regarded themselves, the Uí Bairrche (the strong/brave/battlers) were a Laigin tribe (Laigin a laechMairg), the descendants of Dáire Barrach, son of Catháir Mór, High King of Ireland (†125 AD). O’Rahilly considered the Uí Bairrche to be one of the Érainn or Firbolgs (Fir Belgae) tribes of Leinster. Other similar tribes were the Uí Failge and Uí Enechglaiss. According to a Middle Irish poem in the Book of Leinster, Rus Failge, Dáire Barrach and Enechglas were triplets born to Catháir Mór by the goddess Medb Lethderg, who may have been a daughter of Conan Cualann of Dublin/Wicklow. (‘Clanna Falge Ruis in ríg’). In the will of Cathair Mór from the Book of Rights, the Uí Failge are listed first, the Uí Bairrche second and the Uí Enechglaiss third. |

O'Rahilly proposed four major Celtic invasions of

Ireland: Cruithin/Picts - perhaps the 8th to 5th century B.C. (the Priteni

invading Britain and Ireland) Érainn/Firbolg - perhaps the 5th to 3rd century B.C. (Bolgi or

Belgae from Britain) Laigin - perhaps the 3rd to 1st century B.C. (from

Armorica, invading both Britain and Ireland) Goidel/Gael - perhaps the 2nd to 1st century B.C. (Milesians from Gaul) |

|

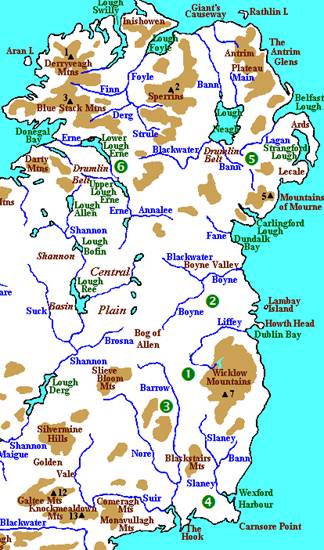

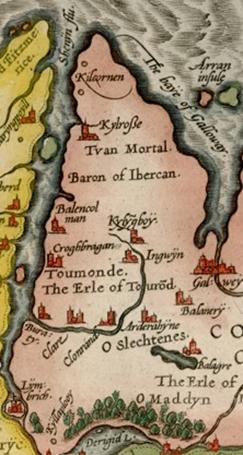

It is commonly thought that the Uí Bairrche

were originally from Wexford, but that their influence extended over a large

part of Leinster up to the end of the 5th century. In the earliest known map

of Ireland, made by a Greek called Ptolemy in the second century AD, the main

tribe of south Leinster were the Brigantes (the exalted). Also the river Barrow is called Birgos or Brigos.

According to O’Rahilly, the Brigante were the Uí Bairrche, who may have been

related to the Brigantes tribe of northern Britain. He also stated that the

name Uí Bairrche indicates decent from a goddess. In the name

of tribes, the eponym can be feminine The godess of the

Brigantii/Brigantes tribes was Brigantia. The Brigantii were described by

Strabo and Pliny as living in the Alps, and was a name attributed to the Alps

themseleves. Some of the main locations were: Aldborough

(Isurium Brigantium) North Yorkshire, England Bragança

(formerly Brigantia) in Trás-os-Montes, northern Portugal. Betanzos (formerly Brigantium), Galicia, north-west Spain: in Roman times; there were Brigantii in Celtiberia. This may be the "Tower of Bregon" mentioned in Lebor Gabala Érenn. (m. Míled Mórglonnaig Espáine qui et nuncupatur mc Nema m. Bili m. Bregaind [Bregon] las ro chumtacht Brigantia &rl. - Rawlinson B502) Brianconnet

and Briançon (formerly Brigantio), both in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur,

France. The town of

Bregenz, at the eastern end of Lake Constance in Austria, retains the older

name of Brigantion, a tribal capital. Brigetio,

Hungary. It is thought that these locations are

not connected to each other, but if they are, it would give an interesting

insight into the migration and dispersal of a celtic tribe. (see Hubert

Butler’s St. Brigid and the Breac-folk). The Brigantes of Britain have also

been called Scotobrigantes, meaning that they came from Ireland and that they

were separate to the other Briton tribes. (Stillingfleet) This may indicated

a migration from Spain to Ireland to Britain. In the ‘Additamenta’ of the

Book of Armagh, it has “Brigitae Ifidarti . Britonisa”. The most likely tribe in the Ptolemy map that would be connected to the Uí

Bairrche, are the Dáirine. They were approximately located in South

Antrim and North Down in the east of Ulster. According to O’Rahilly, the name implies descent from Dáire, and he

states that this shows them to be a branch of the Erainn. It has also been

suggested that the Dáirine had Dáire Barrach as an ancestor deity.

Other tribes, that are thought to have been of the Dáirine, are the sister tribes of Munster, the Uí Fidgeinti and the Uí Liatháin,

who both claimed decent from Dáire Cerbba. Dáre Cherbba is supposed to have been born in

Brega on the north-eastern marches of Laigen territory (Rawlinson B 502).

Also the Munster Traceys are of the Uí Fidgeinti and Tassys are of the Uí

Liatháin. In the Annals, there were references to two major groups, the Uí

Bairrche Maighe (Laois/Carlow/Kildare) and Uí Bairrche Tire (Wexford, thought

to be the barony of Bargy). The genealogies state the Uí Bairrche Maige

hAilbe, Uí Bairrche Tire, Uí Bairrche Mag Argetrois (Laois/Kilkenny), Uí

Bairrche Magh dá chonn (Carlow). In the Annals from 854 AD onwards, it states

Uí Bairrche Maighe and Uí Bairrche Tíre. From 896AD onwards, the references

only state Uí Bairrche. The founder of the Uí Bairrche, Dáire Barraig, was reported to have lived at Dún Aillinne or Cnoc Aulin (Knockaulin) near old Kilcullen, Co. Kildare. Dun Aillin was an ancient fortress of the Kings of Leinster. It was used, along with Tara Co. Meath, as a capital of the Laigin. Archelogical evidence dates it’s occupation from the third century B.C. to the fourth century A.D. It is associated with the rare La Tène celtic influence in Ireland, which originated from western Europe as the Gauls, with it’s height in the fourth century B.C. Emain Macha (Navan Fort) Co. Armagh also has an association with La Tène. Eoghan Mór (Mug Nuadat), the renowned King of Munster was the daltha or pupil of Dáire Barraig, and was fostered at Dun Aillin, when he was forced to flee from his own country. With the aid of Dáire Barraig, he was able to assert his sovereignty in Munster and eventually clashed with Conn Cétchathach (Conn of a hundred battles) King of Ireland from 125 AD. According to Dillon, he got the name Mug Nuadat from his having helped an architect named Nuada who was building the fort of Dún Aillinne. In the death notice for St. Tighearnach, bishop of Cluain Eoais, Keating writes that Daire Barrach was nine years king of Leinster. It has been proposed that Dáire Barrach may have ruled over Tara. In the 7th century poem ‘Baile Chuinn Chétchathaig’, listing the kings of Tara, the following may refer to Dáire Barrach: Conden- Daire

drechlethan –dáilfa doirb mís Dáire

Drechlethan will dispense it in a difficult month The interpretation is that Dáire, a lesser known king of Tara, ruled for a short difficult month. Dáire Barraig (Dáre Trebanda) had three sons, from who are the three free tribes Úi Breccáin, Úi Móenaig and Úi Briúin. The son and grandson of Dáire Barraig, Muiredach Mo-Sníthech and Móenach (Úi Móenaig), were stated as kings of Leinster. Mo-Sníthech was also listed as a King of Ireland in the genealogical poem by Laidcenn mac Bairceda in Rawlinson B. 502. ‘Robo rí hĒrenn Muiredach Sníthe’. Smyth (1975) states that this title also refered to his son Móenach. Con-saíd in rí ruadfoirb

ar-dingg doibsius Ro-bí macco Lifechair Liphi

i lluinhg loigsius. Lonhgais

maro Muiredach Mo-Snítheach sóerchlann sochla sain comarddae

comarbba cóemchlann Con-gab múru mórmaige macrí Móenech márgein the boy-king Móenech a great

offspring took the walls of a great plain It has also been proposed by Carney, MacNiocaill, Charles-Edwards and others, that they both may have ruled over Tara, before the territory of the Laigen was reduced. The Laigen may have been the most important of the early provinces. |

|

||

|

|||

There has also been much speculation as regards the timeframe of the early Leinster kings. O’Rahilly does not believe that Cathaír Már was an actual person but accepts the AU date of 435 (and 436) AD for the death of Bresal Bélach. This date is included in the post-Patrician section of the Annals. This date does not concur with other date references for the kings. Énna Censelach founder of the Uí Cheinnselaig is listed as number 8 in the king lists and Crimthann his son is given as number 9. The death of Crimthann is given in the annals as 465 AD or 484 AD. Eochaid (brother of Cremthan), is stated as living at Tara by Keating, when he was removed by Niall of the Nine Hostages, and whom he later killed in the Loire Valley in France. (†398 or 405 AD).

|

However, the kingship of the Uí Bairrche, descended from another son of Dáire Barraig, Feicc, from who are the Úi Breccáin. There may be a connection between the change in the descent of the kingship and the early legend of the forced migration of the Uí Bairrche. Next in this line was Ailill Móir, who was the maternal antecedent of Saint Colum Cille or Columba (†597AD). It was from another line of descendant of Feicc, Eochaidh Guinech (wounding horse), who reclaimed the Uí Bairrche position in Leinster. An indication of the importance of the Uí Bairrche in the fifth century is given by their influence in religious affairs, their religious figures and the sites associated with them. Unlike most saints of the time, Uí Bairrche saints, came from and were located in the tribal territories. The fist bishop of Leinster, appointed by Saint Patrick, was Fiacc of the Uí Bairrche (415-520AD). In the Bórama it says that he was from Tara before moving to Sleibhte. These clerics were a source of pride for the Uí Bairrche as their genealogies start with a list of their saints. Further details are given below under ‘Saints and Monastic Settlements’. |

Leinster Kings of Tara 1. Cathaír Már King of

Ireland (†125 AD) 2. Fiachu Ba hAiccid 3. Bressal Bélach (†435 AD) 4. Muiredeach Mo-Snithe (Uí

Bairrche) 5. Móenach (Uí Bairrche) 6. Mac Cairthinn (Uí

Enechglass?) 7. Nad Buidb (Uí Dego) 8. Énna Censelach (Uí

Cheinnselaig) 9. Crimthann (Uí

Cheinnselaig) (†465 or 484 AD) |

It is also thought

that likely allies of the Uí Bairrche were the Fotharta or Fothairt, who were

the mercenary tribes of the Laigin and were possibly of Cruithin (Pict) origin.

They were scattered throughout Leinster usually in close contiguity to one or

other of the various groups of the Uí Bairrche. They left their name in the

baronies of Forth (Fothairt in Chairn or Mara or Tire) in southeast Wexford and

Forth (Fothairt Fea) in eastern Carlow. Another interpretation may be that they

were pushed into their territory by the movement of the Uí Bairrche. At a later

date, it may be possible that the Fothairt Mara, on behalf of the Uí

Cheinnsealaigh, drove the Uí Bairrche out of Southern Wexford. In later years,

Uí Lorcán of Fothairt Mara controlled the territory and were Kings of Uí Cheinnsealaigh

in 1024 and 1030 AD. At the time of the Norman invasion, they are listed as

allies of Diarmait mac Murchada King of Uí Cheinnsealaigh and Leinster. In

addition, O Nuallain, likely of Fothairt Fea, inaugurated

Mac Murchadha at Cnoc an Bhogha

(Keating). As already stated, in

the map by Ptolemy, the main tribe of south Leinster were the Brigantes. It is

thought that the map may reflect the tribes of a much earlier time than the

second century. There may be more likely candidates than the Uí Bairrche to be

the Brigantes. For example, in terms of similarities in name there are the Uí

Fidgeinti, who are located in Limerick in historical times, but may have had an

earlier association with Leinster. A sister tribe of the Uí Fidgeinti, were the

Uí Liatháin, who were located around Cork City and perhaps Youghal, which shows

the movement of the tribes. In terms of location and name, the Fothairt could

also have been the Brigantes. They were located on the south coast of Wexford

and the most distinguished member of their race is St. Bridget, foundress of

the church of Kildare. St. Bridgit may have been proto-Irish for Briganti i.e.

High Goddess. One version of her genealogy has her located with the Deisi of Brega.

Early legends tell that the traditional enemies of the Uí Bairrche, the Laigin tribe of Uí Cheinnsealaigh, temporarily drove them out of their territory:

a) According to the ‘Expulsion of the Dési’, the Uí Bairrche of Leinster were driven out by Fiachu ba Aiccid, youngest brother of Dáire Barraig, who gave their territory to the Dési (the allies of the Fothairt), who continued to occupy it until the reign of Crimthann (son of Énna Censelach founder of the Uí Cheinnselaig, son of Labraid, son of Bressal Belach, son of Fiachu Ba Aiccid.), when Eochu Guinech, a famous warrior of the Uí Bairrche, expelled them. Then Crimthann, son of Enna, sent the wandering host of the Dessi to Ard Ladrann (Ardamine, below Courtown) southward. After the death of Crimnthann [by his grandson], his [grand]son made war upon the Dessi, that is, Eochu, took the oak with its roots to them [ie total war]. And in a rout they drove them out into the land of Ossory. It is stated that the wandering of the Dessi was because of their kinship with the Fothairt. Brii mac Bairceda is stated as being either a druid or poet, in the camp of Crimthand. In the Laud 610 version, the Déise were first located in Mag Liffe (Liffey plain).

“the Dessi went to Gabruan (Gabran [Gowran]) and the Féni to Fid Már [Fennagh Carlow] and the Fothairt to Gabruan (Gabran), in the east [Idrone].”

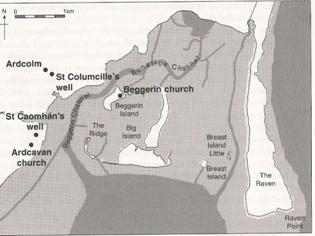

b) According to the Tripartite Life of Patrick (ed. Stokes p.192), Cremthan (son of Censelach), King of Laigin, oppressed them [Uí Bairrche], so that they migrated from their territory, and one of them, Oengus mac Maicc Erca, slew Cremthan in revenge. It is stated that Cremthann gave Slebte and Domnach Mór Maige Criathair (and the island monasteries of Wexford harbour) to Saint Patrick and that Slebte is Cremthann’s burial place. Perhaps this is a reference to the cemetery of Óenach Carman. Saint Patrick then gave Slebte to Fiacc. Slievemargy is called by the older name of Cúil-maige (hill of the Bairrche), which would indicate that it was occupied by the Uí Bairrche. Of interest, the Uí Bairrche are not actually named in this account and Stokes confuses them with the Húi Ercáin of the Fothairt. It also states that “In thirties and forties are the churches which he (Cremthann) gave to Patrick in the east of Leinster and in Húi-Censelaig”, however, all the monastic settlements named are Uí Bairrche settlements. Perhaps this is a piece of Uí Cheinnselaig propaganda, or that it refers to a different Cremthann.

It is also stated that Crimthand Mac Ennae gave to Dubthach Maccu Lugir the territory of Mag Serge to Glais ina Scail (Owengorman or Glas Gorman) which flows by Kilgorman, North Wexford. Part of this territory was the Hill of Formael [Limerick Kilcavan Wexford] which was the territory of Finn mac Cumhal, while Gleann Uissen [Killeshin] located close to Sleibhte [Sleaty] was the territory of Oisin son of Finn mac Cumhal.

In addition, in the version of

the account in the Book of Armagh,

firstly Endae

Cennsalach, banishes Iserninus and Christianity from Leinster. Then Patrick converts

and baptises Enda's son Crimthann, at Ráith Bilech (Rathvilly, in Carlow), and

obtained from him permission for Iserninus and his converts to return from

their exile. Crimthann offers to Patrick for Isernius, part of Ulba in Grian

Fothart from Gabur Liphi [Ballymore Eustace/Blessington/Brittas] as far as Suide Laigen

[Seat of Leinster ie Mount Leinster]. In the ‘Additamenta’ of the Book of

Armagh, the reference to Feicc has “oi bair” written in the margain, and also

has “Echuid Guinech macc Oingoss”.

In another version of the Tripartite Life of Patrick (Ancien Fonds No. 8175) dated to about 1400 AD:

“So he [Patrick] founded abundant churches and

monasteries in Leinster, and left a blessing on Húi Cennselaig especially, and

he left Auxilius in Cell Ausailli and Mac Táil in Cuilenn, and ordained Fiacc

the Fair in Sleibti as the bishop of the province.”

This may mean that at that time, the territory named Uí Cheinnselaig

was located in Kildare, and the three monastic settlements named are Uí

Bairrche settlements

c) Another version, in the genealogies of the Monach or Manach of Ulster [decendants of Ailill Móir of the Uí Bairrche], state that their ancestor Monach, having slain Énna, King of Laigin, left Leinster and betook himself to his maternal uncle, Eochaid Gunnat, King of Ulaid, who gave him land. Mac Fhirbhishigh states that they were descended from Muireadh Snithe in one part and from Féicc in another part.

St. Tigernach, Bishop of Cluain Eui (Clones, Co. Monaghan) (†544-550AD AU) is said to have given protection to the move of the Uí Bairrche tribes to Ulster, as he was their cousin.

With Tighearnach of Cluain Eóis they came

from the south, for he was a brother to their father; the reason for

Tighearnach being in Oirghialla: Dealbhraoch daughter of Eochaidh son of

Criomhthann son of Fiag, son of Daigh Dorn son of Rochaidh son of Colla Dhá

Chríoch, was his mother. And it was with him the Monaigh came on that journey,

for they were under his protection after their killing of the son of the king

of Leinster. (Mac Fhirbhishigh)

A similar version, was that Cairpre Filed [the poet] [Cairbre Ua gCiardha] from whom are Clainn Cairpre in Conmaicne Réin or Sliab Cairpre, had to leave their original territory owing to the slaying of the son of Ennae, the King of Laigin by Echach Guinig of the Ulaid. Clann Ruairc and the Artraighe, of the Monaigh (i.e. Men of the Monaigh [Fear Manach]), are of Cairbre Ua gCiardha of Conmhaicne Magh Réin and Loch Erne.

The Monaig are often associated with the Manapioi (Menapii), a maritime Belgic tribe of Northern Gaul who are noted on Ptolemy's 2nd century map of Ireland in southeast Ireland.

d) According to O’Rahilly, another version by Flann mac Mael Maedóc airchinneach of Gleann-Uisean (†979AD) “Do chomramaib Laigen inso sis” (Rawlinson B 502, S. 88a) of the migration of the Uí Bairrche seems to suggest that it was as a result of the death of Laidcenn mac Bairchid (5th century) of the Ulaid tribe the Dál Araide:

“Ba de sain sóiset fo thuaid ó Inis Coirthi” it was as a result that they (Uí Bairrche?) turned north at Enniscorthy

|

23. Iss é tria gaile

gretha |

Laidcenn, son of Bairchid, was the

chief-poet of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Eochaid (brother of Cremthan) the son

of Enna Cennselach, in revenge for being refused hospitality by the poet,

destroyed his stronghold and killed his only son Leat. Then Niall went on a

raid to Leinster and was given Eochaid as a hostage at Ath Fadat (Ahade “the

long ford”) in Gothart (Fothartaibh) Fea (two miles south of Tullow, Co.

Carlow) on the bank of the Slaney. Eochaid broke his chains and slaughtered his

captors. He was pursued by Niall southward until they reached Inis Fail

(Beggerin Co. Wexford). As the poet began to revile the men of Leinster,

Eochaid killed him with a stone. Later the same Eochaid was responsible for the

death of Niall in France. This tale is also part of Rawlinson B 502, fo. 47a i.

“Orcuin Néill Noígíallaig” (The Death

of Níall Noígíallach) ending with:

|

Aided Néill maic Echach 7 Laidcind maic Baircheda do

láim Kchach maic Énnae Censelaig in sin. Finit. Amen. |

That is the Death of Niall, son of Echu, and of Laidcenn, son of

Baircheda, by the hand of Echu, son of Enna Censelach. Finit Amen. |

O’Rahilly thought that Laidcenn mac Bairchid may have been of the Uí Bairrche due to the similarity of the names. Others have thought that there may have been a connection due the sympatric treatment of the Uí Bairrche by Laidcenn mac Bairchid in the genealogies. Of interest, Brii mac Bairceda, the brother of Laidcenn, was the poet of Cathair Már.

Another connection may be found in the medieval Irish literature of the Ulster (Ulaid) cycle. Cú Chulainn on his jouney to the martial school of Scathach in Scotland, meets Eochaid Bairche, who gives him a wheel and a magical apple to show him the way. In other versions, the figure of Eochaid Bairche is identified as Lugh or Manannán. (Laurie et al)

In the annals the date of the slaying of Crimthann is given as 465 AD or 484 AD, by his grandson Eochaidh Guinech of the Uí Bairrche. Later in 489 AD, Eochaidh Guinech aided the north Laigin Uí Dúnlainge in the battle of Cell Osnada or Cenn Losnada (Kellistown, Co. Carlow), in which Oengus mac Nad Froích, King of Munster and son-in-law of Cremthan, was defeated and slain.

As can be imagined there arrises a certain amount of confusion with the names of Echach Guinig m. Óengussa (Ui Barriche), Eochu Guinech m. Dáire Barraig (Ui Bairrche) and Eochu Gunnat m. Feicc m. Imchada, king of Ulaid and High King of Ireland (Dál Fiatach) (†267 AD). Perhaps, this was an attempt by the genealogists to link these persons. Among the Dál Fiatach kings of Ulaid, there is Bécc Bairrche (†718AD) who gave his name to the Benna Bairche or Boirche (Mourne Mountains). As such, there appears to be a connection between between the tribes of the Ulaid and the Uí Bairrche. Mrs Concannon in her book of ‘The life of St. Columban' describes it as follows:

“Some of their kinsfolk had already settled in the territory of the King of Oirgiolla (Oriel), Eochaid Gundat, whose daughter, Dealbraich, was married to a man of their race, Cairbre. Cairbre and Dealbraich were the parents of Saint Tighernach of Clones—and the exiled sons of MacDaire, found, probably on his account, a welcome in Oriel territory. One of them, Eochaid MacDaire, married a sister of King Eochaid Gundat's wife, herself a Princess of Uladh (of the Dal Fiatach), daughter of Fergus Dubh, and sister of Muirdeach Muindearg. Thus it is easy to understand how there came to be Hy-Bairrche settlements in Oriel and Uladh. Eochaid MacDaire having thus provided himself with two kings as brothers-in-law, felt himself strong enough to return from his exile, and, allying himself with other enemies of the Hy-Cinsellagh, met his grandfather Crimthann in battle, and slew him with his own hands, thus winning for himself the soubriquet of " Guinech " the " Mortal Wounding " and, what is more to the point, the restoration of his ancestral lands.”

This conflict between the tribes is thought to have resulted in the invasion of west Cornwall by the Uí Bairrche and/or the Uí Cheinnsealaigh from Leinster. Also at this time, it should be noted that north and south Wales was colonised by the Laigin (Lleyn), the Deise (Dyfed) and the Uí Liatháin (Dyfed, Gower and Kidwely). The Uí Liatháin are also associated with the Dumnonian Peninsula in Cornwall.

The importance of the Uí Bairrche in the sixth century is

indicated by the marriages recorded. Corbach

(Corpach) daughter of Maine, a descendant of Muiredach Mo-Snítheach, married (Fergus) Cerrbél of Clann Cholmáin.

She was the mother of Diarmait mac Cerbaill, High King of Ireland (†565AD).

Another important marriage was that Eithne

(also known as Derbfhind Belfhota) of Ros Tibraid, an Uí Bairrche princess to

Feidimid, great-grandson of Niall of the Nine Hostages and prince of the Uí

Néill dynasty of high kings. This is recorded as she was mother to St Colum

Cille or Columba (†597AD) considered to be the one of the three great saints of

Ireland with St. Patrick and St. Bridget. In the record of her genealogy, there

is Cairpre the poet [Cairbre Ua gCiardha of Conmhaicne Magh Réin and Loch

Erne], whom Keating describes as king of Leinster, and his father Ailill the

Great, who is described as King of Ireland in the Book of Lecan. She was a

descendant of Féicc.

In the second half of the sixth century, a prominent King of Uí Bairrche, Cormac mac Diarmata (mac Echach Guinig of the Uí Breccáin, of the royal line of the Uí Bairrche), is named a number of times in the hagiography and is shown as a ruthless ruler of south Leinster. The Lives of St. Abbán of Adamstown, St. Cainnech of Aghaboe (†600AD), St. Finnian of Clonard, St. Fintain of Clonenagh (†603AD) and St. Comgall of Bangor (†602AD), refer to Cormac mac Diarmata as king of Leinster or of Uí Cheinnselaig (an anachronism for king of South Leinster). There is also a similar reference in the genealogical tracts, but not in the king lists. O’Hanlon, in the Lives of Irish Saints, states that his father Diarmata was also king of Uí Cheinnselaig. Extracts from the lives of the saints are given in the references below:

The Life of St. Fintan states that he freed Cormac mac Diarmata when he

was imprisoned by Colmán mac Cormac Camsrón of Uí Cheinnselaig at Rathmore (one

mile south of Rathvilly, Co. Carlow). In this account Colmán mac Cormac Camsrón

is styled king of north Leinster. The AFM state that Colmán mac Cormac died at

Sliabh Mairge in 576AD. The Life states that Colmán mac Cormac was killed before the end of the month. Cormacus, the son of Diarmoda,

lived for a long time in the kingdom of the Laginians, and in his old age, at

the end of his holy life, at the abbot of St. Comgallus, in the province of

Ulster, in the monastery of Beannchor, he ended his holy life.

In the Life of St. Abbán, Cormac mac Diarmata is stated as attacking Abbán's monastery of Camaross, south-east of Adamstown Co. Wexford, and the implication is that it lay within Uí Bairrche territory.

In the Life of St. Cainnech of Aghaboe, Cormac mac Diarmata is shown as practising the savage custom of gialcherd (treatment of hostages) or gallcherd (foreign art). The life is thought to contain several important references to social customs. Aghaboe located in west Laois and Saigir in west Offaly were both churches of the Osraige and were only displaced by Cell Cainnich (Kilkenny) after the coming of the Normans.

In the Life of St. Finnian of Clonard, Finnian lands at the portus

Kylle Caireni (thought to be Carne Wexford) where he is meet by

Mureadach filius Engussa (Uí Felmeda of Uí Cheinnselaig), then he goes to Achad

Abla (Aghold in the barony of Shilelagh, Wicklow) near Barche. He then spends

seven years in Mugny (Moone, Kildare). In Uí Bairrche, King Diarmidh

is dead, and his sons, Cormac and Crimthan, share the rule over the Uí

Bairrche, and they were jealous of one another. Crimthan was the elder, Cormac

the more subtle of the two. Cormac visited his brother and spoke strongly

against Finnian as a man of a grasping nature, and urged him to expel the Saint

from his territories. Crimthan went to the church where Finnian was, and

ordered him to leave. The Saint refused and a scuffle ensued, in which Crimthan

stumbled and broke his ankle on a stone; and Finnian cursed him that his

kingship should come to naught. In Stokes’ version of the Lives of Saints this

section is missing.

This Crimthan is not included in the genealogies.

There is a reference in the Life

of Munnu of Taghmon (after 600 AD) to a Criomthan, king of Ui Cheinnselaig and

Leinster, who is also not included in the king lists. This Criomthan had a son

Aedh Slaine, who was murdered by Ceallach, the son of Dimma Mac Aodh, king of

the Fotharta who had a fortress near Achadh Liathdrum/Taghmon. In the genealogies, Dima mac Áeda is listed

as being of the Fothart Maigi Ítha of south Wexford. The ensuing battle takes

place at Bannow and may described the expulsion of the Fothart from this part

of Wexford. King Crimthan is stated as being located at the island of Liachan/

Liac hAln [grey rushes?], whose location has not been identified and may refer

to the sloblands of Wexford.

The lands of the monastery of Dísert Diarmata (Castledermot, Co. Kildare) was apparently donated to the monastery of Bangor by a king of Uí Bairrche, who had been a disciple of St. Comgall. “Cormac (mac Diarmata), King of Leinster, bestowed Imblech nEch on Comhgall of Bendchuir (i.e. Bangor)”. Smyth (1982) identifies Imlech Ech as Cenn Ech (Kinneigh) to the east of Castledermot. According to the Life of St. Comgall he also had three castles; Carlow town on the Barrow, Foibran (Sligo or Westmeath?) and Ard Crema (Wexford). This is perhaps the earliest reference to Carlow town. The Irish name for Carlow is Ceatharloch which is officially translated as four lakes, but there is no evidence of these lakes. A more likely rendering of the name is Catharlogh (the spelling stated on early maps), which would be translated as stone or monastic enclosure on the lake. O’Hanlon, in the Lives of Irish Saints, states that this lake was located between Carlow town and Sleaty located two miles to the north. Foibran may be a monastic settlement in Sligo. Smyth states that the Laigin had settlements in north west Connacht. Also when Fiacc met St. Patrick he was coming from Connacht. It may also be the monastic settlement of Foibrén (Foyran, north Westmeath). At the end of Cormac mac Diarmata reign, he left his kingdom to become a monk with St. Comgall at Bangor. In the Life of St. Comgall, we are told that he was overcome by homesickness, but did not abandon his pious exile:

“He dreamt that he had been walking round the borders of Leinster visiting his beautiful cities and fortresses, and that he had traversed the flowering plains and lovely meadows; he dreamt of his kingdom and of his fine war-chariots and he saw himself surrounded by his war-lords, princes and magnates, and with the symbols of his royal power.”

According to Shearman, Cormac mac Diarmata had a son called Gorman or Gordmundus who styled himself King of Ireland, and who invaded England as described by Geoffrey of Manmouth. This may be based on the entries in Thady Dowling, Chancellor of Leighlin, Annales Breves for 590AD for Gurmundus, the chief pirate of the Norwegians, an African by nationality, who acquired Ireland from the Norwegians. Burchardus son of Gurmundi otherwise known as O Gormagheyn, duke of Slieve Margi and Leinster, and who he stated was responsible for the foundation of the catherdral of Leighlin. Burchard may be of Germanic origin from burg "castle" and hart "hard".

This Gorman may

explain the placenames of Loch Garman (Wexford harbour), Kilgorman (north

Wexford) and Gormanstown (south Wicklow). On the origins of the name of the Fair of

Carman in Leinster, one explaination was that it was the grave of Old Garman.

In the epic tale of Táin Bó Cúailnge, Cú Chulainn and Ferdiad recall the

battles they had with Germain the Terrible in Thrace.

In the ‘Lives of

British Saints’, it is stated that Gorman, son of Cormac Mac Diarmid, king of

the Hy Bairche, who in the

middle of the sixth century destroyed Llanbadarn Fawr and other churches, and

did much havoc in Britain. The monastry [Amesbury], according to Camden,

contained three hundred monks, and was destroyed by “nescio quis barbarous

Gormandus”. Geoffrey of Monmouth converted him into a king of Africa. See John Lynch (Cambrensis eversus Volume 3) for more information on this.

In the Carew Manuscripts (The book of Howth), there is a reference to Gormondus, King of Ireland circa 400 and 586 AD, who invaded England and France. In reference to King Henry’s invasion of Ireland, it is styled ‘Irland of Gormon’. In Ware and Spenser, he is called Gurmondus, a Rover out of

Norway, who after invading England and Frances, invaded

Ireland and became King of Ireland. Gurmund(us)

is also included in Giraldus Cambrensis ‘The Topography of Ireland’.

Heywood (1600s), styles him Gormondus King of Africa, German Worm and Sea Wolfe, who first invaded Ireland, and thence was invited by the Saxons, to assist them against the British Nation. He then invaded France with Isimbardus the nephew to Lewis the French King. Koptev, in an explanation of the French chanson de geste, named ‘Gormond et Isembard’, details the invasion of France by the Saracen king Gormondus from England.

Gorm King of Denmark who died circa 958 AD was also known as Gormondus. He died of grief on hearing that his son Canute was killed in an attempt to capture Dublin. Beckmann gives a list of the name Gordmundus in France from around 1170 onwards, where it is an alternative version of the name Warmundus. For example, there is Warmundus or Gormondus of Picquigny, the Patriach of Jerusalem (1119-1128)

In the seventh century, a King of Uí Bairrche was Suibne mac Domnaill (grandson of Cormac mac Diarmata). In the Life of Munnu of Taghmon (†635 AD), it would appear that he

controlled the area of Leighlin at the time of the synod over the ordering of

Easter (630 AD). It is stated that Munnu, as a result of being insulted by

Suibne, prophesised that his head would be cut off by his brother’s son (Cind

Faílad?) and would be thrown into the Barrow, near the Blathach stream (Madlin

River?). His brother Faílbe married Eithne daughter of Crundmael mac Rónáin

(†656 AD) king of Uí Cheinnselaig and Lagen Desgabair (South Leinster) and

Mugain, the daughter of Faílbe, married Cellaig Cualand, King of Leinster (†715

AD) from whom are the Uí Cellaig Cualand. There is an entry in the Annals of

Ulster recording the death in 766 AD Cernach son of Flann who is also thought

to be of this line.

There are some

parellels to Suibne in the romantic tale 'Buile Suibne' (‘madness’ of Suibne).

In the tale, Suibhne Geilt is king of the Dal Araidhe of Antrim. He states that

he killed Oilill Cédach, king of the Uí Fáeláin at the battle of Magh Rath (637

AD) [near the river Lagan] along with five sons of the king of Magh Mairge. In

the end he is saved by St. Moling at Tech Moling, (St. Mullins Co. Carlow).

|

|

|

Ancient

Genealogy of Uí Treasaig, kings

of the Uí Bairrche 36.

Milesius of Spain. 37.

Heremon: son of Milesius. 38.

Irial Faidh ("faidh": Irish, a prophet): his son 39.

Eithrial: his son; was the 11th Monarch; reigned 20 years; 40.

Foll-Aich: his son; 41.

Tigernmas: his son; was the 13th Monarch, and reigned 77 years; 42.

Enboath: his son. 43.

Smiomghall: his son; 44.

Fiacha Labhrainn: his son; was the 18th Monarch; reigned 24 years; 45.

Aongus Olmucach: his son; was the 20th Monarch; 46.

Main: his son; 47.

Rotheachtach: his son; was the 22nd Monarch; slain, B.C. 1357, by Sedne (or

Seadhna), of the Line of Ir. 48.

Dein: his son; 49.

Siorna "Saoghalach" (long-oevus): his son; was the 34th Monarch; he

obtained the name "Saoghalach" on account of his extraordinary long

life; slain, B.C 1030 50.

Olioll Aolcheoin: son of Siorna Saoghalach. 51.

Gialchadh: his son; was the 37th Monarch; slain B.C. 1013. 52.

Nuadhas Fionnfail: his son; was the 39th Monarch; slain B.C. 961. 53.

Aedan Glas: his son. 54.

Simeon Breac: his son; was the 44th Monarch; slain B.C. 903. 55.

Muredach Bolgach: his son; was the 46th Monarch; slain B.C. 892; 56.

Fiacha Tolgrach: son of Muredach; was the 55th Monarch. slain B.C. 795. 57.

Duach Ladhrach: his son; was the 59th Monarch; slain B.C. 737. 58.

Eochaidh Buadhach: his son; 59.

Ugaine Mór: his son. 66th Monarch of Ireland. slain B.C. 593 60.

Laeghaire Lorc, the 68th Monarch of Ireland 61.

Olioll Aine: his son. 62.

Labhradh Longseach: his son. 63.

Olioll Bracan: his son. 64.

Æneas Ollamh: his son; the 73rd Monarch. 65.

Breassal: his son. 66.

Fergus Fortamhail: his son; the 80th Monarch slain B.C. 384. 67.

Felim Fortuin: his son. 68.

Crimthann Coscrach: his son; the 85th Monarch. 69.

Mogh-Art: his son. 70.

Art: his son. 71.

Allod (by some called Olioll): his son. 72.

Nuadh Falaid: his son. 73.

Fearach Foghlas: his son. 74.

Olioll Glas: his son. 75.

Fiacha Fobrug: his son. 76.

Breassal Breac: his son. 77.

Luy: son of Breassal Breac. 78.

Sedna: his son; 79.

Nuadhas Neacht: his son; the 96th Monarch. 80.

Fergus Fairgé: his son; 81.

Ros: son of Fergus Fairgé. 82.

Fionn Filé ("filé:" Irish, a poet): his son. 83.

Conchobhar Abhraoidhruaidh: his son; the 99th Monarch of Ireland. 84.

Mogh Corb: his son. 85.

Cu-Corb: his son; King of Leinster. 86.

Niadh [nia] Corb: his son. 87.

Cormac Gealtach: his son. 88.

Felim Fiorurglas: his son. 89.

Cathair Mór, Monarch of Ireland 120 to 123 AD,: his son. 90.

Dáire Barraig: his son. 91.

Féicc: his son. (brother of Muiredach Mo-Sníthe, King of Leinster) 92.

Breccáin: his son 93.

Meicc Ercca: his son. 94.

Óengussa: his son. 95.

Echach Guinig: his son. 96.

Diarmata: his son. 97.

Cormaicc: his son. 98.

Domnaill: his son. 99.

Suibne: his son. 100.

Máel h-Umae: his son. 101.

Coibdenaig: his son. 102.

Echach: his son. 103.

Gormáin: his son. 104.

Dúnacáin: his son. 105.

Gussáin: his son. 106.

Luachdaib: his son. 107.

Tressaig: his son. (from whom are Uí Tresaig) 108.

Áeda his son. 109.

Donnchada his son. 110.

Muircherdaig his son. 111.

Gormáin his son. 112.

Meic Raith (died 1042) his son. 113.

Muiredaig his son. 114.

Gussán his son. 115.

Óengus and Muircheartach his sons. Or 103.

Arttgaile his son. 104.

Fócartai his son. 105.

Beccáin his son. 106.

Tressach (King of Ui Bairrche Maighe slain 884 AD) (from whom are Uí

Tresaig) 107.

Braon his son. 108.

Beacán his son. 109.

Braon his son. 110.

Beacán his son. 111.

Colga his son. |

|

From the middle of the ninth century, there are numerous entries for Uí Bairrche Maige and Uí Bairrche Tire in the Annals of the Four Masters, which may be an indication of their importance and the extent of their lands. It is probable that that they were copied from a source similar to the Fragmenary Annals, i.e. a local account. At that time, a prominent king of the Uí Bairrche was Tressach, son of Becan, King of the Uí Bairrche Maighe. He is remembered in the Annals of the Four Masters and also in poems in the Book of Leinster (46a and 47a), ‘A Bairgen ataí i nhgábud’ (The Quarrel about the Loaf) and ‘Dallán mac Móre: Cerball Currig cáemLife’. He would appear to the source of the Tracey family name. He was regarded as a hero of Leinster and the ruler of the river Barrow (Tressach Berba barr). In ‘Deoraidh sonna sliocht Chathaoir’ the genealogy poem of the MacGormans in Co. Clare, he is described as Cú Chulainn. According to the annal he died in 884 AD: Treasach, son of Becan, chief of Uí Bairrche Maighe, was slain by Aedh, son of Ilguine. Of him Flann, son of Lonan, said: A heavy mist upon the province

of Breasal, Heavy the groans of Assal, Wearied my mind, moist my

countenance, The annal states that Treasach was killed by Aedh son of

Ilguine who may have been of the Uí Bairrche. However, he is not named in the

genealogies and the entries in the annal are confused. Ilguine is a very rare

name and the only reference found may indicate that it has an Ulaid origin.

In the Annals of Ulster (U883 & U886), there are references to Eolóir son of Iergne, who is thought

to have been an aggressive leader of the Vikings of Dublin, who may be a more

likely candidate. In the Icelandic

Book of Settlements, Landnámabók, there is a reference to Thrasi and his son

Geirmund. Cerball Mac Dúnlainge, also known as Kjarvalr Írakonungr

(Kiarval/Kjarval) (842–888) King of Osraige, has a prominent place in the

Icelandic sagas and in the genealogies of the founding families of Iceland as

recorded by the Landnámabók. It has been suggested that the importance of

Cerball in Icelandic writings stems from the popularity of the Fragmentary

Annals of Ireland among the Norse-Gaels of eleventh century Ireland. The

section of the Fragmentary Annals that would have dealt with the death of

Tressach are missing. It would interesting to speculate, given the timeframe

and the close proximity of the Osraige, the connection between the Barrow

River and the Vikings, that Thrasi and his son Geirmund, may have been based

on Tressach and Gorman of the Uí Bairrche. An indication of Treasach’s importance is that his memorial was written by Flann mac Lonan (†891 or 918 AD), the Vergil of Ireland and chief poet of all the Gael. He was killed by the Ui Fothaith at Waterford harbour. (See also: ‘Flann Mac Lonain in Repentant Mood’ and ‘Eulogy on Ecnechan son of Dálach King of Tír Conaill †906 by Fland mc Lonain ollam Connacht ‘Ard do scela a meic na cuach’ Ed. J. G. O’Keeffe, Ir. Texts 1 (1931) 22-24, 54–62., A Story of Flann mac Lonáin, transcribed by 0. J. Bergin. Anecdota from Irish Manuscripts, Vol.1, p.45) http://www.ucc.ie/academic/smg/CDI/PDFs_textarchive/IrishTexts1.pdf http://www.ucc.ie/academic/smg/CDI/PDFs_textarchive/AnecdotaIpt2.pdf The ‘province of Breasal’ may be a reference to Bressal Brecc, the common ancestor of the Laigin and Osraige and as such refers to all parts of Leinster. The reference to ‘fortaliced Liphe’ may refer to the first Viking settlement on the Liffey at Islandbridge in Dublin. According to O’Cróinín (1995), the Irish did not have a name for the settlement at that time. In 866 AD Conn, son of Cinaedh, lord of Uí Bairrchi Tire, was slain while demolishing the fortress of the foreigners, which may also have been Dublin or Arklow/Wicklow or Wexford harbour. Assal may be a reference to one of the sons of Úmór, mythical leaders of the Fir Bolg, who had a magical spear. As such, it may be a combined reference to the Fir Bolg and the Laigin, whose name was derived from the spears they carried. Or it may be a reference to Meath, perhaps the Hill of Skryne. In the Oxford Reference, it states “A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann who owned a magical spear, the Gáe or Gaí Assail, and seven magical pigs. His spear was the first brought into Ireland. It never failed to kill when he who threw it uttered the word ‘ibar’, or to return to the thrower when he said ‘athibar'.” ‘Oenach Lifi’ refers to his funeral feast on the Liffey,

which is another indication of his importance. Edmund Hogan equates Oenach

Life with Oenach Colmáin in Mag Life and Oenach Clochair. Oenach Colmáin was

a burial place of the Munster and/or Leinster princes. Ó Murchadha also

equates Oenach Life with Oenach Colmáin. Oenach Life has also been equated

with Óenach Carmain. Of interest Oenach

Colmáin, has been identified with early Uí

Fidgenti references, from who are the Traceys of Munster. Another reference in the annal

to Oenach Lifi is AFM 954AD “A

hosting by Conghalach, son of Maelmithig, King of Ireland, into Leinster; and

after he had plundered Leinster, and held the Fair of the Liffe (aonaigh Life)

for three days, information was sent from Leinster to the foreigners of

Ath-cliath; and Amhlaeibh, son of Godfrey, lord of the foreigners, with his

foreigners went and laid a battle-ambush for Conghalach, by means of which

stratagem he was taken with his chieftains at Tigh-Gighrainn.” Also there is

the poem Oenach indiu luid

in rí/ Oenach Life cona li

(Today the king went to a fair/ The

fair of Liffey with its lustre or

Finn and the phantoms), whose geographical locations centre on the Liffey and

Munster. (van Kranenburg) According

to O’Donovan, in an interpretation of an extract from the Book of Leinster,

there were ancient roads from the Liffey to Slievemargy and Magh Airgead-Ros

i.e. Bealach Gabhruain followed by Belach Smechuin and also the Gabhair which

separated Laighin Tuath-Ghabhair and Laighin Deas-ghabhair (north and south

Leinster). In King Aldfred’s Poem (circa 685 AD), the lands of the Laigen are

described in terms of Athcliath to Sliabh Mairge. The last line gives his eminence amoung all the Laigen, and the reference to the sea refers to the rest of Ireland. |

||

|

|

There are a number

of townland place names that are derived from the Traceys of the Uí Bairrche.

In Carlow, there is Tracey’s crossroads on the border of Carlow and Forth

baronies. In Kildare, there are Baltracey (5 kilometres north of Clane on the

road to Kilcock), Baltracey and Newtown Baltracey (3 kilometres south east of

Naas) and Tracey’s crossroads (just south east of Kildare town). These

locations also reflect Uí Bairrche monastic sites. In Kilkenny, there is

Kiltrassy (Killamery/ Windgap). In the Fiants of Edward VI, there is a

references to Rory Trassy of Butlerswood, which is in the same civil parish.

There is also a reference that Kiltrassy (Cill Dreasa) is named after a Saint

Teresa of Spain, of whom there is no record. In Wexford, there is Ballytracey

(Boolavogue, east of Ferns) and possibly Traceytown East and Traceytown West

(south-east and west of Taghmon), which could be of Norman origin. In Down,

of peculiar interest, there is the Trassey Valley in the Mourne Mountains

(Benna Bairche or Boirche). These townlands and placenames may be an indication of the boundaries of Uí Bairrche influence at the

time of Treasach. Clane and Naas (3 & 4), are both close to the Liffey

river where he died and had his funeral feast. In addition, he was King of

the Uí Bairrche Maighe and he ruled the Barrow, presumable around Carlow

town.

|

|

‘Bal’ or ‘Bally’ is the anglicised form of the Irish

word ‘baile’ which roughly translates as town or townland. It is thought that

its use dates from the middle of the Twelfth century. ‘Kil’ can be the

anglicised form of the Irish word ‘Cill’ meaning church or ‘Coill’ meaning

wood.

Also at this time, the church in Leinster seems to have administered from Gleann Uisean. In 916 AD at the battle of Ceannfuait (close to Leixlip, Co. Kildare) Arch-bishop of Leinster and Abbot of Gleann-Uisean, Maelmaedhog son of Diarmaid was killed. The reference to the rank of arch bishop or even bishop of Leinster is very unusual. He was of the Uí Chonandla of the Ui Buide/Uí Maelhuidir of the Dál Cormaic.

It has been stated that it may not have been until late in the ninth century that Uí Cheinnselaig domination of the lower Slaney in Wexford was complete. In the Annals, the last reference to Uí Bairrche Tire was in 906 AD. In the account of the Cath Bealaigh Mugna 905AD, it states that Cleirchén king of Uí Bairrchi came from Inis Failbe, which may be Inis Fail (Beggarin) on the north side of Wexford harbour. The poem in the Book of Leinster (46a), ‘A Bairgen ataí i nhgábud’ (The Quarrel about the Loaf), about these battles names Ciarmac Slane rí Fer na Cenél, which is the name given to the north side of Wexford harbour. Of interest, the leaders of Uí Bairrche Tíre in the annals are not named in the genealogies. It has been proposed that the Uí Dróna of Uí Cheinnselaig, , located on the Barrow river, broke the power of Uí Bairrche by moving southward, seizing the Slaney valley from Rathvilly to Tullow, thereby separating the Uí Bairrche of Laois/Carlow/Kilkenny from those of Wexford. In 906AD (AFM) Aedh, son of Dubhghilla, lord of Ui-Drona of the Three Plains, Tanist of Ui-Ceinnsealaigh, was slain by the Ui-Bairrche. Of interest, the poem of his obituary has him described as the just king of the land of peaceful Fearna in Wexford rather than the traditional St. Mullins on the Barrow in Carlow. Previous references in the annals have the various septs of the Uí Cheinnselaig fighting for control of Ferns. The control of Ferns may have been a requirement for the kingship of Uí Cheinnselaig.

By the eleventh century, it is thought that the main body of the Uí Bairrche were located in the middle of Leinster, close to their allies the northern Laigin. This probably reflects a lack of references to their other territories which can be found in the Rawlinson B502 genealogies, which was probably written around this time. Their main area of control is the barony of Slievemargy (Cuil maigi, Cull maige, Mairg Laighean, Slievemarragy, Slievemarigue, Sleamerg, Sliabh Mairge, Sliabh Maircce, Temair ‘Tara’ Mairghe) (Sliabh mBairche = mountain of the Bairrche) in the south-eastern corner of Laois and the adjoining portions of Carlow and Kilkenny. Mairg is thought to have extended as far south to the present town of Belach Gabrán (Gowran Co. Kilkenny) and has been identified with the Ossraige. The Metrical Dindshenchas states two accounts for the origins of the name for Sliab Mairge; firstly, the death of the Lady Marg, and secondly that it is derived from Marga, the son of Giustan, Lawgiver of the Fomorians, who was killed on the mountain. Temar Mairge and Glenn Uissen (cell glinne uissen, Clunussi, Killeshin, Killuskin, Usenglind) were the birthplaces of Fin Mac Cumhal and of his son Uissen. In the will of Cathair Mór from the Book of Rights, the Uí Bairrche are stated to live near Gowran, on the southern frontier of their allies, the Uí Dúnlainge as a barrier to the Uí Cheinnselaig:

“Sit on the frontier of Tuath Laigin (north Leinster);

Thou shall harass the lands of Deas Ghabhair (south Leinster);”

It should be noted that

the Uí Dúnlainge and the Uí Cheinnselaig are not named,

but rather their ancestor Fiacha Baiced. This leads Symth (1975) to belive that

the original text was revised to include him, to surplant the prominace of the Uí Failge.

However, the Book of

Rights seems to have a northern Laigin emphasis. The Uí Bairrche are located

between the Uí Drona and the Uí Buide and receive the following from the King

of the Laigin:

“Eight steeds to the Ui Bairrche for their vigor,

‘Twas but small for a man of his (their chieftain’s) prowess,

Eight drinking-horns, eight women, not slaves,

And eight bondmen, brave [and] large.”

but unlike other

tribes, except the Uí Dhúnlainge, they do not pay a tribute in return. However,

this section does not seem to have been completed according to tradition.

There are no references to any participation by the Uí Bairrche in the battles of Brian Boru, including the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, which was fought against their allies. However, in the previous winter of 1013 (AFM 1012), it is recorded that he camped at Sliabh Mairge, and plundered Leinster as far as Dublin, to which he laid siege. It would be interesting to speculate that this may have been the start of an alliance between the Dál gCais and the Uí Bairrche. It may also be that he got his nickname from the river Barrow. Earlier connections may start with Saint Dolue Lachdere, who was saved from Cormac mac Diarmata by Saint Cainnech, and went on to found a monastic settlement at Killaloe, Co. Clare. St. Comgan (†569AD) second abbot of Glenusssin, was of the royal line of the Dál Cais. Finally the MacGormans moved to Clare and became the marshals of the O'Brians. Trassach as a name also appears in the Dál Cais genealogies.

The next leader that is referenced in the annals was Donnchadh mac Aedh, King of the Uí Bairrche. In 1024 AD, he defeated the men of Munster at Gleann Uisean (through the miracles of God and Comhdan i.e. Comgan of Killeshin). Kuno Meyer published a poem under the heading of Wirtshausreime from B. IV 2 (R. I. A.). It may have been composed to commemorate the battle with the Munstermen. In the poem there are quatrains from the sons of the kings of Uí Bairrche, Uí Drona and Fotharta, which were located immediately to the south and east of the Ui Bairrche in County Carlow. I presume that the sons were fosterlings or hostages of the Ui Bairrche, united against a common enemy. In 1041 AD, he took Faelan Ua Morcha, lord of Laeighis (Laois) prisoner, whom he delivered to the King of Leinster, Murchadh mac Dunlaing (of the Kildare Uí Muiredaig), who blinded him. Also in 1041 AD, Domhnall Reamhar, (i.e. the Fat), heir to the lordship of Uí Cheinnsealaigh, in a preying excursion into Uí Bairrche was slaughtered by Murchadh mac Dunlaing at Cill-Molappoc (Kilmolappogue, Lorum, Co. Carlow). Also Fearna-mor was plundered by Donnchadh mac Brian, and Murchadh mac Dunlaing. In revenge for both of these, Gleann-Uisean was plundered by Diarmait mac Mael-na-mbo of Uí Cheinnsealaigh, and the oratory was demolished, and a hundred were killed and several hundred were carried off as prisoners. In 1042 AD, in the battle of Magh-Mailceth in Laois, Donnchadh mac Aedh and Murchadh mac Dunlaing were killed by Gillaphadraig mac Donnchadh, lord of Osraighe (Kilkenny), and Cucoigcriche Ua Mordha, lord of Laeighis, and Macraith Ua Donnchadha, lord of Eoghanacht (west Munster). Also slain in this battle was Gilla-Emhin Ua h-Anrothain, lord of Ui-Cremhthannain (east Laois), and Eachdonn mac Dunlaing, Tanist of Leinster with many others.

Ó Corráin (1974) in

his examination of ‘Caithréim Chellacháin Chaisil’, thinks that the Donnchad

mac Aeda, king of Fotharta listed, is otherwise unknown unless he is to be

identified with Donnchad mac Aeda meic Tressaig of Uí Bairrche. However, the

dates do not tally as the event described occurred about 950 AD. In addition,

there is a reference to a Bran Berba, son of Amalghadh, king of Omagh and of Ui Mairgi.

He is not included in the genealogies as are a number of other figures listed.

At this time, the Uí Cheinnselaig became the dominant tribe of Leinster and by the eleventh century they had taken over the kingship of Leinster from the Uí Dúnlainge, the allies of Uí Bairrche.

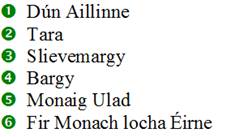

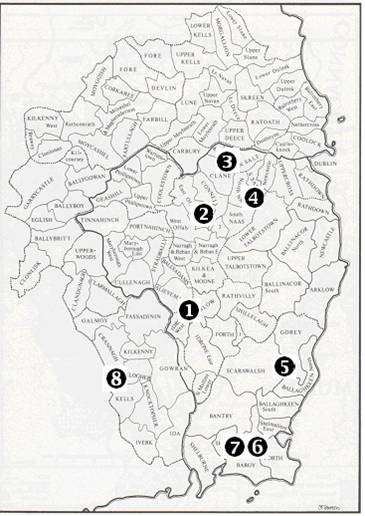

The chief representatives of the Uí Bairrche in historical times were the Uí Treasaig (Tracey) and Mac Gormáin (MacGorman). MacFhirbhishigh makes particular reference, in the following order to Uí Mhaoil Umha of the royal line, Mac Gormáin kings of Uí Bairrche, Uí Threasaigh of Uí Bairrche Tire and the royal line, Uí Cearnaigh (O’Carny, O’Kearney) of Magh Dhá Chonn, Uí Domhnaill (O’Donnell), Ua mBrocain (O’Brogan), Uí Móenaig (from Móenach son of Muiredach Sníthe) (Mooney) of Loch Erne, Síol Cumaine (Cummin), Monaig Ulad (Mooney of West Co. Down), Manaigh locha Éirne (Mooney of Loch Erne), Uí Caindeachain (O’Canahan?) kings of the Monaigh. In the annals, the Uí Treasaig were were cited as Kings and lords of Uí Bairrche, and latterly, the MacGormain were cited as lords of Uí Bairrche. This reflects the diminishing power of the Uí Bairrche. Both were cited as Lords of Slievemargy by historians.

The first reference to the Tracey surname in the Irish Annals was in 1008AD, where it states, "Gussan, son of Ua Treassach, lord of Ui-Bairrche, died." Also in 1042 Macraith, son of Gorman, son of Treasach, lord of Ui-Bairrche, and his wife, were slain at Disert-Diarmada, by the Ui-Ballain (Ballon, Carlow derives its name from Ui Ballein, a tribe of the Fotharta). His wife was Doireand, daughter of Artúr Clérech of Uí Muiredaig. In the twelfth century, the MacGormáin family name appears to have superseded the Uí Treasaig family name as leaders of the Uí Bairrche, though perhaps not in Wexford. The MacGormain name is first referenced in 1103AD and in 1124AD where the annals state “Muireadhach Mac Gormain, lord of Ui-Bairrche, who was the ornament and glory, and the chief old hero of Leinster, died.” Extraordinarily in the genealogies in Rawlinson 502, there are two strands in the Uí Bairrche king lists, the first includes two references to ‘Gormáin’ and one to ‘Tressaig’. This strand continues in the annals and is also the genealogy of the MacGormans of Co. Clare. The second, shorter strand gives prominence to ‘Tressach mac Beccáin’. Perhaps this was meant to reflect the change in kingship although neither of the surnames are included. This may explain the reference to "Macraith, son of Gorman, son of Treasach". This may also explain the adoption of ‘Mac’ by the Gormans and ‘Ua’ by the Traceys. Of interest, there appears to a strong DNA link between the two families as some members of both families have a very rare mutation, DYS392=11.

An entry in the Annals of Tigernach for the year 1116 AD states that the monastic community of Kildare (Kildare town) were slaughtered by the Úi Bairrche. This may indicated a break with the Uí Dhúnlainge and that they had a presence in the area. O’Corráin (2005), states that due to the plague and famine of 1113-6 AD, a number of monasteries were attacked at this time. The various annals for 1116 AD list a large number of monasteries that were attacked and the Annal of Ulster also includes the following:

U1116 There was a great pestilence; hunger was so widespread in Leth Moga, both among Laigin and Munstermen, that it emptied churches and forts and states, and spread through Ireland and over sea, and inflicted destruction of staggering extent.

|

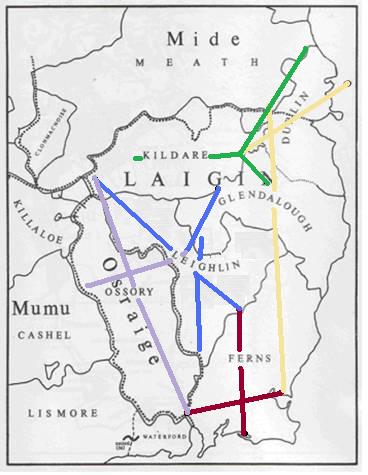

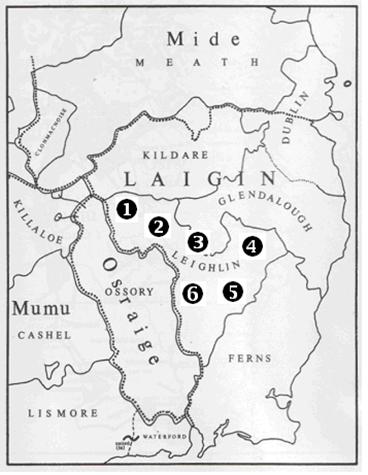

It is thought that

the synod of Rath Breasil (circa 1111AD) convened to set out the dioceses of

Ireland, may give an indication of the tribal territories and their

influences at the time. However, the dioceses of Leinster seems to reflect

more the centres (and main saints) of the church. There are a number of

interesting boundary markers: Slievemargy lies between

the dioceses of Kilkenny and Leighlin, and Leighlin extends to Kilcullen. As

such, it is presumed that St. Laserian of Leighlin was the most important saint of the

area and that Sleaty’s claim to the Patrician centres such as Kilcullen was

still in force. Naas, a centre of

political power, lies between the dioceses of Kildare and Glendalough. Begerin Island lies

between the dioceses of ‘Ferns or Loch Gorman’ and Gendalough, indicating

that the east coast of Wexford was under the control of the diocese of

Glendalough. One might speculate that Ardcavan (Wexford Harbour) and Kilcavan

(Bargy and Gorey) as placenames, might have been the result of the influence

of Glendalough. These three areas are also in Uí Bairrche territories. The

use of ‘Ferns or Loch Garman’ is also interesting, in that it may infer that

St. Aidan of Ferns and St. Ibar of Begerin were held in equal esteem. The

latter dominance of Ferns may have been the result of the influence of Diarmaid

Mac Murchadha in religious affairs. The medieval diocesan boundaries, resulting from the Norman conquests may be a better indicator of tribal territories. The diocese of Leighlin is thought to include the lands of the Laígis, Uí Buide, Uí Bairrche, Uí Felmeda, Fortharta and Uí Dróna. This gives an indication of the land held by the Uí Bairrche at this time. |

Synod

of Raith Breasail (A.D.

1110 or 1118): Diocesan Boundaries markers in Leinster

|

Medieval Diocesan Boundaries (Smyth 1982)

|

1204 Confirmation to Herluin, bishop of Leighlin, and his successorsf Lighlin, Cluam, Eidnec, Thechmochna, Techmoedoch, in Nuaconghail, Domnachescrach, Tulach, and Collabbain, Sruthar, Glondussen, Cetorlocth, Slebre, Glorach, Cluaitiencia,dechllin, Missel, Berrech Athfadat, Cellasnad, and Artingenaeda,rcn Durtrichalaa, Cellederggidam, Radmor, Tilachfortchin, Cluammormoedoc Dimcsinti, Rathilec and Cellmecchatil ; in the parish[e3 of] Hubargay, Hubuy, Leys, Hofelmebt, Fodereth, OdroD, with Thathmolig ; with their churches possessions anddign. of their possessions, namely, the city oe Achadarglaiss, Jumaide,

Cal. Papal Letters i 18

In 1124AD the annals state “Muireadhach Mac Gormain, lord of

Ui-Bairrche, who was the ornament and glory, and the chief old hero of

Leinster, died.” This is an interesting epitaph, but no other direct references

to him have been found. He may be the MacCorman (MacGormáin) referenced in the ‘Book of Durrow’ describing a land agreement

between Killeshin and Durrow, and the grantor of Baltinglass.

It is thought that an original grant of land to the Cistercian abbey of Baltinglass (Belach Con Glais) in the first half of the 12th Century was made by an Irish King, MacCorman (MacGormáin) before the conquest of Ireland, possibly in the form of a charter. According to the 1397 inquisition at Carlow, the land granted were the granges of Grangeford, Wryghteston (or Cluan Melsige possibly Clonmelsh) and Carrigtoman (or Cartuamain possibly Chapelstown). In the confirmation charter to Baltinglass by King John in 1185, the following lands were stated as being part of ‘Ua Barche or Barthe’: Dumetham, Chapelstown, Agaddarith, Godwin’s mill & Killamaster.

This would indicate, as might be expected, that the barony of Carlow formed part of Uí Bairrche territory, along with the adjoining barony of Slievemargy. The Norman cantred of Obargy in Katherlough (Carlow) was listed with the town of Katherlough, although Empey’s illustration of the cantreds includes it in Idrone along with the barony of Carlow.

It has been suggested that the manuscript Rawlinson B502

also known as the Book of Glendalough was written at Killeshin in 1130AD, which

may explain the detail given to the Uí Bairrche genealogies. Their king list

comes second after the Uí Cheinnsealaigh. Their genealogies are the first of the Laigin decended from

Cathair Mór, which is repeated in the Book of Ballymote and the Book of Lecan.

Also the poems in Rawlinson B502 appear to have an Uí Bairrche bias. The Book

of Leinster differs from Rawlinson B502 in that the kings list only has one

strand, and has an extra generation. Their genealogies do not have a heading

but are at the start under the heading of “De Genelach Dail Nia Corbb”.

One reference states that the Uí Bairrche dynasty appears to have been deprived of these remaining territories in 1141AD by Diarmait Mac Murchada of the Uí Cheinnselaig, during a purge of the chief families of Leinster, including three sons of MacGorman (Annals of Tigernach)

1141AD Diarmaid Mac Murchadha, King of Leinster, acted treacherously towards the chieftains of Leinster, namely, towards Domhnall, lord of Ui-Faelain, and royal heir of Leinster, and towards Ua Tuathail, i.e. Murchadh, both of whom he killed; and also towards Muircheartach Mac Gillamocholmog, lord of Feara-Cualann, who was blinded by him. This deed caused great weakness in Leinster, for seventeen of the nobility of Leinster, and many others of inferior rank along with them, were killed or blinded by him at that time.

After this period the Uí Bairrche are not recorded in the Irish Annals. “A country without a chief is dead.” Ní ba tuath tuath gan egna, gan egluis, gan filidh, gan righ ara corathar cuir ך cairde do thuathaibh.

There is, however, a reference in the annals for 1585AD to the descendants of Daire Barach, the son of Cahir More, that they were amoung the list of Leinstermen who would not attend the call to Parliment in Dublin.

|

In the annals in 1095, there was a great pestilence in Ireland which killed a quarter of the population including Cairpri ua Ceithernaigh the noble bishop of Ua Cheinnselaigh. Roderick O’Trassy is listed as one of the Bishops of Ferns, Co. Wexford during the period 1117 to 1155 AD. His name is listed on the wall of St. Aiden Cathedral, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford as Rodericus O’Tracey †1145 AD. His position would indicate that the Traceys and the Uí Bairrche still held some power in that area at that time. It is stated that in 1166 AD Diarmait Mac Murchada, burned his capital of Ferns under threat of invasion by Rory O’Conor of Connacht. Of interest, up to that time, in the list of Bishops of Ferns there appears to be a number of surnames that may be of Uí Bairrche origin, which would indicate that the area may have been under their influence e.g. O’Kearney and Ballycarney on the Slaney, 3 miles west of Ferns, O’Treacy and Ballytracey four miles south east of Ferns, and O’Cahan. As such, Diarmait Mac Murchada may have burned Ferns in anticipation of a revolt on his home front. Uí Bairrche lands in Wexford seem to have been claimed by the church of Ferns, after this time. The above named lands formed the boundaries of the ‘Manor’ of Ferns as described after the Norman invasion. Ballytracey may have become the property of the church, similar to nearby Ballyregan, as the result of the resolution of a dispute in 1226-7 between John de St. John, Bishop of Ferns and the Prendergasts of Enniscorthy. In addition, Bargy was also claimed by Ferns. According to Colfer, Hervey de Montmorencey c1200 granted extensive lands in Bargy to the Cistercians. The last Irish Bishop of Ferns, Ailbe Ua Maelhuidhe, contested this grant claiming that they belonged to Ferns. By an agreement of c.1230, Canterbury retained the lands and church livings of Kilmore, Kilturk, Tomhaggard, Kilcowan, Bannow, Killag, Carrick and the Saltee Islands, all in the cantred of Bargy. |

Bishops of Ferns (Flood,

Lanigan, Ware, AFM)

Cairbre O’Kearney †1095AD Cellach O’Colman †1117AD Maeleoin O’Donegan †1125AD or Carthag O'Magibay Maelisu O’Cahan †1135AD Rory O’Treacy †1145AD Brighidian O’Cahan †1172AD (resigned) Joseph O’Hay †1185AD (of

the Uí Deaghaidh of Uí Cheinnselaig) Ailbe O’Molloy, O.Cist. †1222-3AD (last Gaelic bishop)

De Episcopis Fernensibus, extract from

Ware 1665 |

The Uí Rónáin (Ronane or Royane) of Tig Mo Sacro are also considered to be an ecclesiastical family according to historians. The saint Mosachar is thought to have been the abbot of Clonenagh (Cluain-eidhneach) in Laois, Saggart (Tigh Sacra near Tamlacht) in Dublin, and Fionn-mhagh in Fotharta. There is some confusion that Tig Mo Sacro is in Saggart rather than Tomhaggard in Wexford. It is thought that Fionn-mhagh was an earlier name for Tomhaggard. There are also references to Cluain-Dolcáin (Clondalkin), which are outlined in Doherty. In 885 Ronan, son of Cathal, Abbot of Cluain Dolcain died. In 938, Duibhinnreacht (Dercc n-Argit in genealogy???), son of Ronan, Abbot of Cluain-Dolcain died. In 1076, an army was led by the clergy of Leath-Mhogha (South Ireland), with the son of Maeldalua, to Cluain-Dolcáin (Clondalkin) to expel Ua Ronain, after he had assumed the abbacy, in violation of the right of the son of Maeldalua. It was on this occasion that a church, with its land, at Cluain-Dolcain, was given to Culdees for ever, together with twelve score cows, which were given as mulct to the son of Maeldalua. However, in 1086, there is the reference Fiachna Ua Ronain, airchinneach of Cluain-Dolcain, died. In 1162, Cináed Ua Rónáin (or Celestino) (†1173AD) was bishop of Glendalough when he witnessed Diarmait Mac Murchada’s charter to Ferns and also his charter granting Baldoyle to Edanus, Bishop of Louth. The name Ronane or Royane is still most common around Wexford.

|

Finn mac Gussáin mac Gormáin Bishop of Kildare who died in 1085 AD would have been of the Uí Bairrche. Bishop Finn of Kildare who died in 1160AD was an important religious figure. He is thought to have commissioned and to have been one of the scribes of the “Book of Leinster”. In the Book of Leinster he requests to have the book of poems of [Flann] mac Lonan. He may have been of the Mac Gormain of Uí Bairrche as in the annals he is named as “Mac Gormain” and “Ua Gormain”. Also there are very few references to the Uí Bairrche in the “Book of Leinster”. In the Martologies, on October 25, there is “gentle Gormán of the metres. in Cell Gormáin in

the eastern part of Leinster.” This is thought to be Kilgorman, north

Wexford, which was an Uí Bairrche settlement. The Ua Gormain were an important ecclesiastical family and there are a number of references to the family in the Annals and other sources. In the Annals of Clonmacnoise, this Gorman family are stated to be descended from Conn Mboght, the eranaghs of Clonmacnoise and related to the O'Kellys of Brey. [Breagha east Meath] (see also King). In the Book of Kells, one of the charters thought to have been written about 1100AD, refers to “oa gormán ó claind conaill” [O'Gorman of the Clann-Conaill], who would have been located near Kells, Co. Meath. Another reference in the Book of Lismore, states that the Hí Gormáin are located in Mallow, Co. Cork and that Clenur is their burial ground. |

M610.5 Gorman, one of the

Mughdhorna, from whom are the Mac Cuinns, and who was a year living on the

water of Tibraid Fingin, on his pilgrimage at Cluain Mic Nois, died. (O'Donovan notes:

"Gorman.—He was of the sept of the Mughdhorna, who were seated in the

present barony of Cremorne, otherwise called Mac Cuinn ua mBocht, Erenaghs of

Clonmacnoise, in the Kings County. In the Annals of Tighernach, the death of

this Gorman is entered in the year 758." Tibraid Finghin was a well at

the edge of the Shannon River at Clonmacnoise.) M753.6 Gorman, successor of

Mochta of Lughmhagh [Louth], died at Cluain Mic Nois, on his pilgrimage; he

was the father of Torbach, successor of Patrick. M807.18 Torbach, son of Gorman,

scribe, lector, and Abbot of Ard Macha, died. He was of the Cinel Torbaigh, i

e. the Ui Ceallaigh Breagh; and of these was Conn na mbocht, who was at

Cluain Mic Nois, who was called Conn na mbocht from the number of paupers

which he always supported. Scannlan, son of Gorman

(†918AD), wise man, excellent scribe, and Abbot of Ros-Cre; Ua Ruarcain, airchinneach

of Airdne-Caemhain [Wexford haven]; and Gorman Anmchara [soul friend], died.

(†1055AD) Donnghal mac Gorman

(†1070AD), chief lector of Leath-Chuinn, and Tanist-abbot of Cluain-mic-Nois;

U1070 The son of Gormán, lector of Cenannas [Kells], and sage of Ireland, died. Finn mac Gussáin mac

Gormáin (†1085AD) Bishop of Kildare, died at Cill-achaidh [Killeigh Geashill

Offaly]. Aenghus Ua Gormain

(†1123AD), successor of Comhghall, died on his pilgrimage at

Lis-mor-Mochuda.* Finn Mac (or Ua) Gormain

(†1160AD), Bishop of Cill-dara, and who had been abbot of the monks of

Iubhair-Chinn-trachta [Newry] for a time, died. (Finan M’Tiarcain O’Gorman

Tr.Th.) Maelcaeimhghin Ua Gormain

(†1164AD), master of Lughmhadh, chief doctor of Ireland, and who had been

Abbot of the monastery of the canons of Tearmann-Feichin for a time, died. Máel Muire Ua Gormáin

(c.1167AD) abbot of Arrouaisian house of Knock, Co. Louth (author of

Martyrology of Gorman) Flann Ua Gormain (†1174AD)

arch-lector of Ard-Macha and of all Ireland, a man learned, observant in

divine and human wisdom, after having been a year and twenty learning amongst

the Franks and Saxons and twenty years directing the schools of Ireland, died

peacefully on the 13th of the Kalends of April [March 20], the Wednesday

before Easter, in the 70th year of his age. * May have been the uncle of St. Malachy of Armagh (Africa) |

|

|

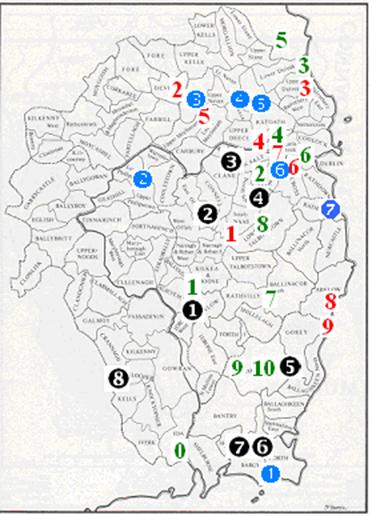

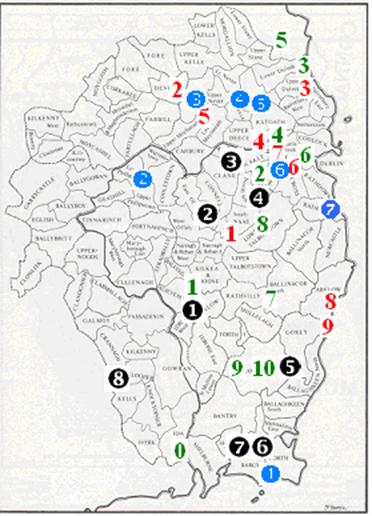

It is not known exactly when the Traceys families

dispersed. They could have been displaced by the mac Gormáin, or by Diarmait

Mac Murchada of the Uí Cheinnselaig or by the Normans. In the 19th

century the majority had settled in the general area of North Tipperary,

Offaly, Laois and North Kilkenny, where they are still numerous today. Their

descendants are the most numerous Traceys in Ireland. Roughly 10% of the

Traceys in Ireland are located in the barony of Ikerrin in North

Tipperary/South Offaly. Perhaps the migration trail followed the Noir river

from North Kilkenny. They also settled in the other surrounding Leinster

counties of Kildare, Carlow, Westmeath, Wicklow, Dublin and Wexford. There

are also early reference for the eastern seaports of Drogheda (Louth), Dublin

and Arklow (Wicklow). It may be presumed that the Traceys of Louth are also

of the Uí Bairrche, as there is also a high prevalence of Carneys and Gormans

in that area. There is also a high

prevalence of Traceys in the Ui Enechglaiss territory of Arklow. Richter

states that the Leinster kings had royal fleets, which may account for the

presence of Traceys in these seaports. The historian Peadar

Livingstone expresses an opinion that the Traceys of Fermanagh are not

natives to Ulster. It seems possible that these Traceys were also of the Uí

Bairrche, as there is a connection to Fermanagh in the genealogies. Also it

is reported that both Traceys and O’Gormans were termoners (ancient church

wardens) in Fermanagh (Mac Murchaidh et al). It may

also be possible that the Uí Bairrche Traceys migrated across the Shannon to

become a sept of Sil Anmchadha where the name is referenced in 1158 AD. The Uí Bairrche may have had a settlentment

in east Galway as described in the placenames by Flann mac Lonan. It seems

likely that Fermanagh and Galway were earlier Uí Bairrche settlemts and that

Ikerrin was settled at a later date. Ikerrin has a lower number of Gorman

families, which may reflect a later conflict between the ruling

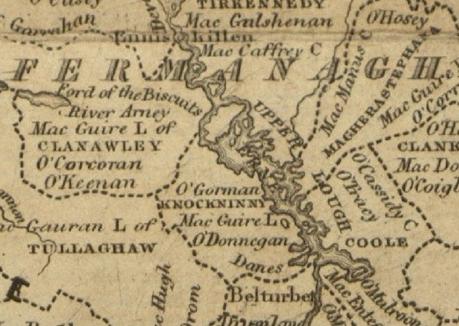

families. In the ‘Topographical and Historical Map of Ancient Ireland’ by Philip

Mac Derrmott in 1846, the O’Tracy Fermanagh Clann and the O’Gormans are

located either side of Upper Lough Erne. |

The mac Gormáin settled in Monaghan and Tipperary (Doire Seinliath or Senlaith in Uaithne (Owney) [perhaps Derryleigh - Doire Liath, Kilvellane Tipperary, Owney-Cliach Limerick/Tipperary]. In the Sheriff’s Accounts for Tipperary 1275-6, there is a ‘wealthy’ Richard Makgorman living in Carrick-on-Suir (although Curtis seems to think this is an Ostman or Irish Danish name). In the Red Book of Ormond for 1300AD, there is a reference to ‘terra McGorman’ in Carkkenlis (Carkenlys = Caherconlish) Limerick.

In south Tipperary, below Caher on the border with Waterford, there is the civil parish of Ballybacon (Baile Uí Bhéacáin) containing the townlands of Gormanstown and Kilballygorman. Also located nearby is the townland of Tincurry, usually found in Uí Bairrche settlements.

|

Some moved to Dál Cais (Clare), and were noted as chiefs of Tullichrin (Uí Breacain, a name taken from one of the free tribes of the Uí Bairrche), a territory comprising parts of the baronies of Moyarta and Ibrackan. As early as 1168 (to 1185), Scanlan mac Gormáin is recorded as a witness to a charter by Domnall Ua Briain, King of Thomond to Holy Cross Abbey. In an agreement between Killeshin and Durrow in the late eleventh/early twelfth century, it states that land had been given to the Dál Cais. Keating states in the History of Ireland, that:

The inference being that MacGorman were in Dál Cais before the Norman invasion. The

timeline of genealogy poem of Mac Bruaideadha would also support this. Their chiefs became marshalls (military commanders) under the O’Briens, where they acquired great wealth and influence and there are numerous entries in the annals. In 1563, an account of their movement to Munster is given by Maelin Og Mac Bruaideadha (Mac Brody), chief poet of the Ui Breacain (O’Gorman) and Ui Fearmaic (O’Grady). The parish of Kilfarboy in West Clare was known in 1302 as Kellinfearbreygy or Kellinfearbuygy, in 1394 as Killnafearwary and later as Kilforbrick and Kilfearbaigh. (Church of the men of Bargy). There is a reference to cleric ‘William Marchomayn’ who held a benefice in1486 at Kilfarboy vicarage. (Luke McInerney 2011). The next parish is Kilmurry Ibrickan (Cill Muire ó m-Bracáin - Church of Mary at Ibrickan AFM 1599). There is also the following reference: Donn Macormain .i. Bicaire Cell Muire Udacht Muirchertaigh mic Mathghamhna in aimsir a Chais co bfiadhnaise dona Sagartaibh, Ix. 8; ¶ this is Kilmurry Ibrickan p. and vil., c. Clare. 120 bó ag Donn Macormáin ar na tabhairt do Muircheartach Mac Mathghamhna a ngeall ar leathceathramhain daire an crosain, Ix. 9. (Ix. = I. 6, 13, T.C.D.; O'Curry's copy of 13 vellum

Deeds.) (Meic Gormain paid a tribute of 120 cows to

the Meic Mhathghamhna lords of Corkavaskin - Luke McInerney 2011) Listed

in a 1555 papal bull for Clare Abbey [Ennis] is the vicarage of Ogormaie or Ogormane,

which Luke McInerney (2011) identifies as Drumcliffe [west of Ennis]. It is

signed by MacCrath [McGrath] of Brican or Kylbrigan [Kilbreckan, Doora east

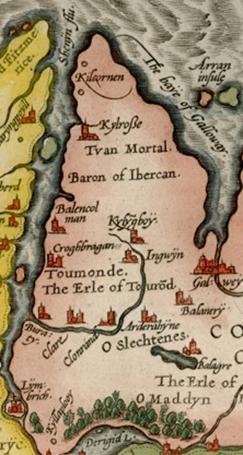

of Ennis]. The Meic Craith were a leading ecclesiastical family in Co. Clare. In the map, Hiberniae

Britannicae Insulae Nova Descriptio by Abraham Ortelius, Antwerp 1587, the

following are included in the area of County Clare, the land

of the 'Baron of Ibercan' and at the tip a town called Kilcornen. |

|

Other historians suggest that the Uí Bairrche were driven out of their lands by the Norman invaders, a fate endured by many other clanns. The Annals of Clonmacnoise state that battle between Dermot McMurrogh with his Norman allies won against the Ossarians took place at Slieve Mairge after which they retired to Loughlin. It is generally thought that the Norman invasion in 1169AD landed at Bannow, part of the Uí Bairrche territory in Wexford: